Mark Synnott

New York Times bestselling author and journalist; author of three nonfiction books; pioneering big wall climber and one of the most prolific adventurers of his generation; works with The North Face Global Athlete Team (of which he has been a member for more than two decades); a highly sought after storyteller and motivational speaker; also an IFMGA certified mountain guide, a long time SAR member and first responder, and a trainer for the Pararescuemen of the US Air Force

I knew it was Alex’s dream to be the first to free solo El Capitan — I just never thought it would actually happen. When I took him on his first international expedition to Borneo in 2009, he confided to me that he was thinking about it. In the ensuing years, Alex joined me on more climbing expeditions, to Chad, Newfoundland, and Oman. Along the way, I experienced many classic “Alexisms,” like him explaining at the base of the wall in Borneo why he didn’t climb with a helmet, even on dangerously loose rock (he didn’t own one); or the time in Chad’s Ennedi Desert that he sat yawning and examining his cuticles while Jimmy Chin and I faced down four knife-wielding bandits (he thought they were little kids). Perhaps the most classic Alexism of all occurred below a 2,500-foot sea cliff in Oman, when he strapped our rope to his back and told me that he’d stop when he thought it was “appropriate to rope up” (the appropriate place never appeared). But Alex and I also spent countless hours talking about philosophy, religion, science, literature, the environment, and his dream to free solo a certain cliff.

I often played his foil, especially when it came to the subject of risk. It’s not that I’m against the idea of free soloing – I do it myself on occasion. I just wanted Alex to think about how close he was treading to the edge. Like most climbers, I had an unwritten list of the people who seemed to be pushing it too hard – and Alex Honnold was at the top. By the time I met him, most of the other folks on my list had already met an early demise (and the rest weren’t far behind). I like Alex, and it didn’t seem like there were many people willing to call him out, so I felt okay playing the role of father figure. And Alex didn’t seem to mind. In fact, it seemed as though he enjoyed engaging me on the topic of risk, and he climbed over my arguments with the same skill and flair with which he dispatched finger cracks and overhangs. What it all came down to was that for Alex Honnold, a life lived less than fully is a fate worse than dying young.

I looked over at my two sons, still peering through the tram window, eager to ski. Alex was only twenty-nine years old. If he allowed himself to make it to my age, he might have more things outside of himself to live for; presumably his desire for risk would diminish in kind – as it had for me.

But most of all, I wondered, now that Jimmy had burdened me with the knowledge that this was happening, what I should do about it. Should I try to talk Alex out of it? Could I? Or should I support this mad enterprise and help him achieve his dream?

from The Impossible Climb by Mark Synnott (Dutton, 2020)

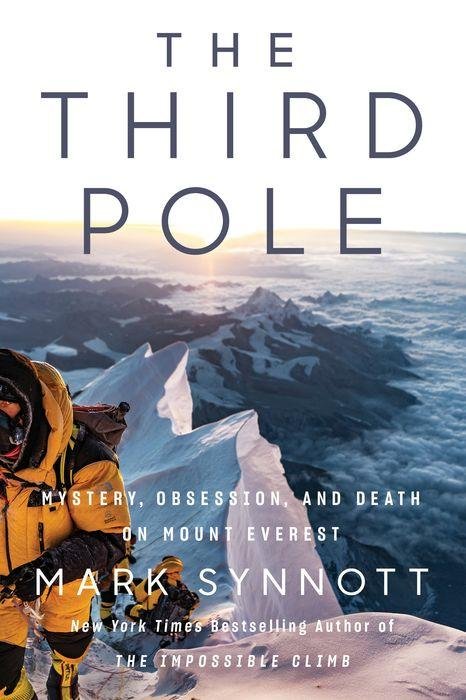

Latest Release:

Dutton, April 2021